During the Covid-19 lockdown, it has become starkly apparent to all of us that the digital world is the future – the future of communication, work, education, and recreation. In order to relax and boost their mental health, people turned to the digital versions of their favourite museums, gardens, and theatres, and of course relied on the already digital world of ebooks, movies, and television. For many museums, including Headstone Manor, it has thrown into sharp relief the importance of digisation and online learning.

Of course, Headstone Manor was already in the process of ‘going digital’, which greatly helped us when we had to move onto social media to interact with our ‘visitors’! Those of you who have visited the Museum in person before will have interacted with our touchscreen content, much of which is pulled from the physical collections we hold. Lucy Wheeler, who held the position of Digitsation Project Officer from 2017-2019, kick-started an ambitious project to digitise the 10,000+ photos held by the Harrow Local History Collection & Archive. This project is still ongoing, and we hope to have over a thousand of them recorded by the end of the summer.

But what is digitisation, exactly? And what does a digitisation officer do?

For many people, digitsation of objects such as old photographs or slides simply means scanning them and saving them on a hard drive or CD. For a digitisation officer, however, that is only one step. Our main concern is long-term digital preservation and access, which at its most basic is a four-stage process.

- Select and transfer

Just as we do not accept every physical object that is offered to the Museum, we also do not accept or save all digital content offered to us, or even created by our own team.

During this phase, we decide if the digital content offered to us is relevant to our collecting process, if it is coming from an external donor. This includes checking the size of the digital content, checking for viruses, and transferring the digital content from an outside device onto our own workstations.

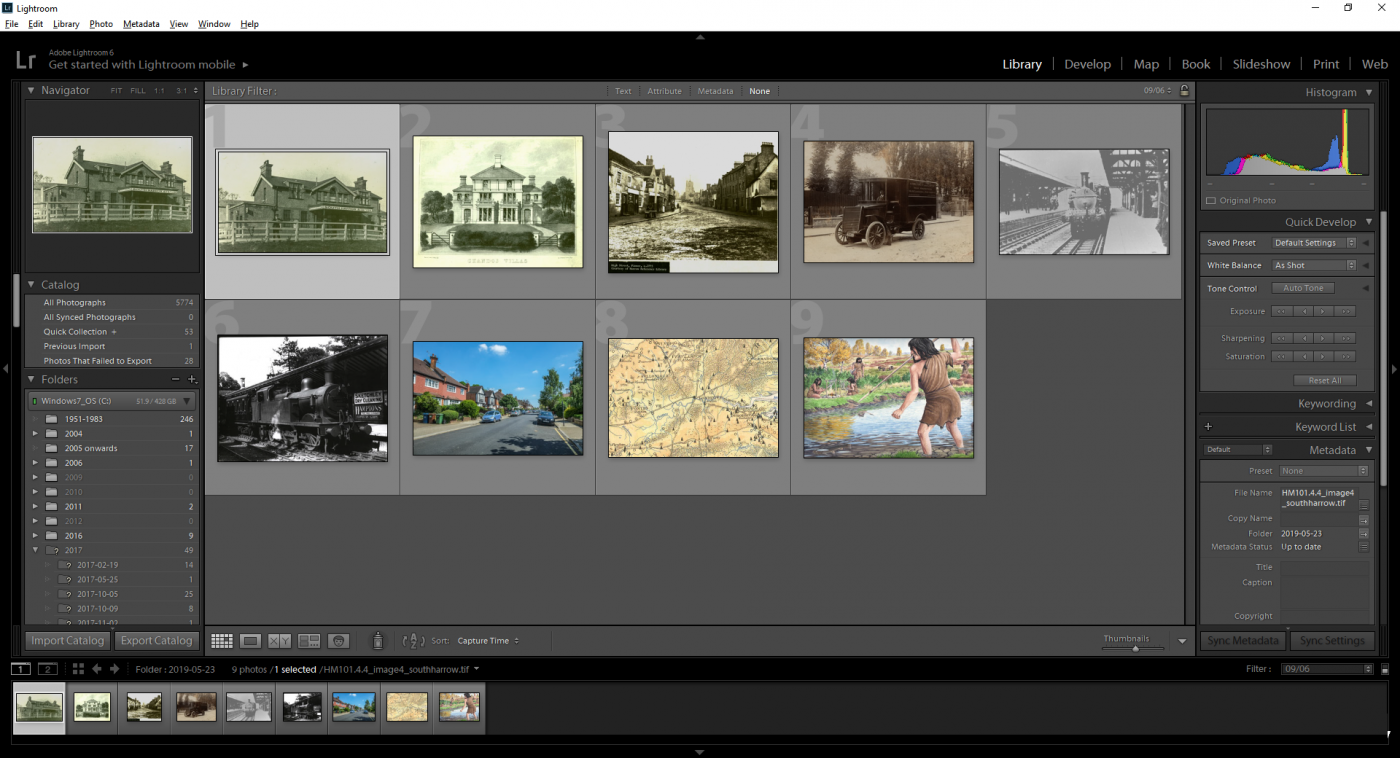

If it is an internal project, like Lucy’s, we decide how is best to digitally capture the information we need about the physical object. For three-dimensional objects, this is usually a large photography project which is undertaken with professional studio equipment in our Workroom. For paper based objects, we typically scan them, and if they are too fragile or large to be scanned, we can photograph them. However, in some cases the objects are far too large – some of our maps are up to 3 metres wide! In this situation, we would send the maps to external companies who specialize in fragile and/or large scale digitisation. We also send objects out if we do not have the right equipment – for instance with film reels. After the photographs or scans are made, we must ensure that the quality and colour are true-to-life, editing the photos until they are accurate representations of the object captured, often using software such as Adobe Lightroom and Photoshop.

- Ingest

During the ingest phase, we record information about the digital content, which is called metadata. We make a list of all the files we have, what type of files they are, how big they are, what software is needed to open and read them, when they were last modified, etc. This can be done by hand or using automated software like The National Archive’s DROID, which is then later proofread by staff.

We also record information about the digital content itself – what is it, what does it show, who made it, when it is it from. All of this metadata can be saved in our catalogue, and will help future users of the digital content to understand how it works and why it is important.

This is also the time that we note any legal restrictions – copyright, GDPR, etc., and put processes into place that ensures the material is used correctly in the future.

Stay tuned for the next blog to find out the last two processes…