No doubt many of you are aware of the tragic Rail Disaster which occurred at Harrow & Wealdstone Station on 8th October 1952. 112 passengers and railway staff died and over 150 were injured when two collisions occurred, involving three trains. The fact that this occurred in the midst of a busy urban community meant that there was a rapid response from the emergency services. The official report records that the first ambulance and doctor arrived within three minutes of the collisions occurring, closely followed by the Fire Brigade and the Police.

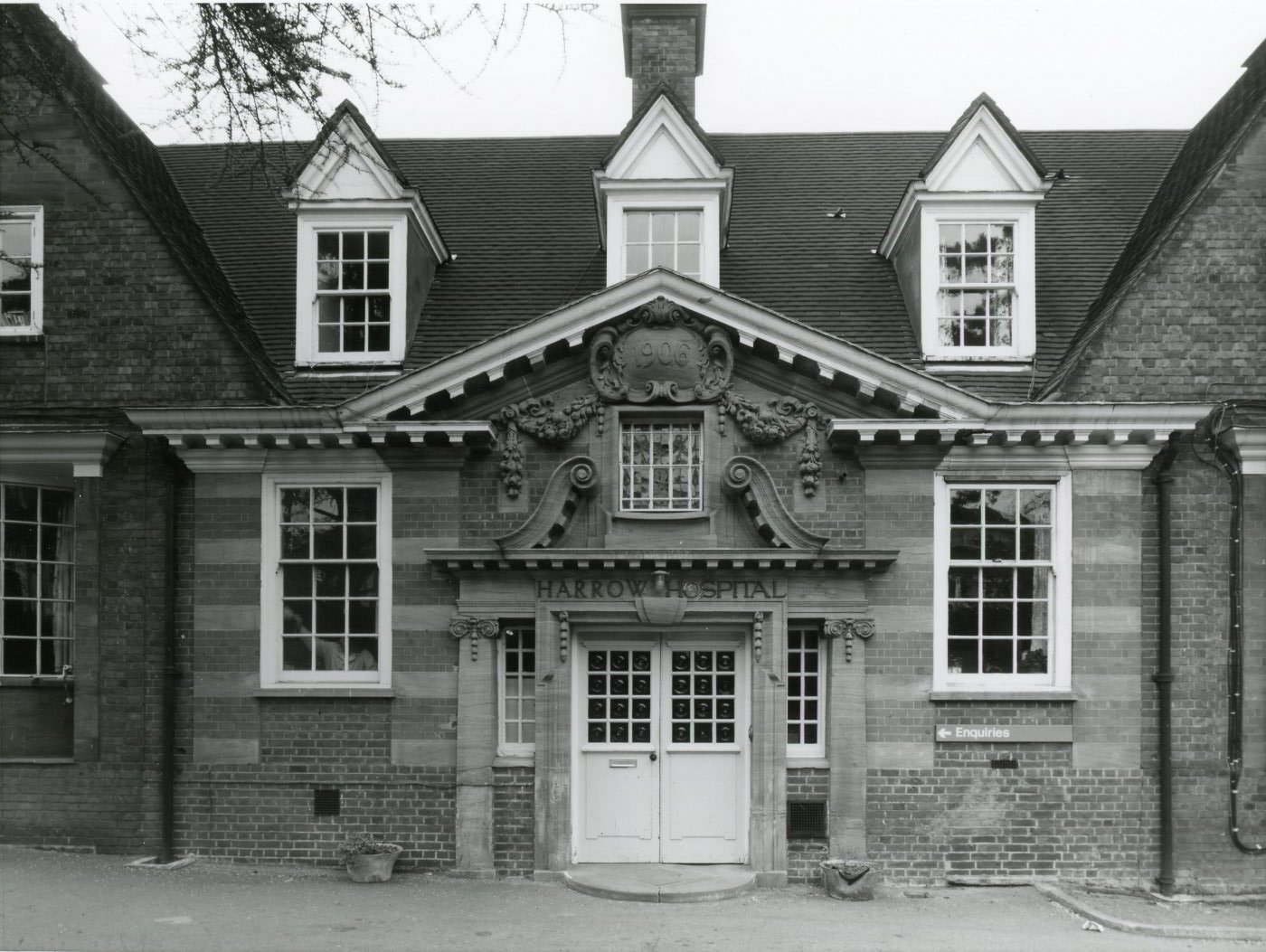

Harrow Cottage Hospital (or Harrow and Wealdstone Hospital as it was known at this time), on Roxeth Hill was one of the closest to the scene. It had an Operating Theatre and 160 beds. However, it only had a small Casualty department and it would be another twenty years before Northwick Park Hospital would be opened. As a nurse working at the Cottage Hospital at the time recalls “The first we heard of it was whilst serving breakfast at about 8:30, when we heard ambulance bells ringing as they came up the hill. We were told to discharge home immediately all patients fit to go home. When the ward was cleared and we were told to lay mattresses on the ward floor”

The Headstone Museum has the logbook for the Operating Theatre at the Hospital, covering the period of October 1952, among its acquisitions. This document tells a similar story. The relevant page starts with the routine operations of the 6th and 7th October being recorded. But the entries for 8th October are quite different. It is clear that something unusual is occurring. The next four entries are all patients involving injuries requiring distal limb fracture repairs. They occupy the theatre from 10:30am to 5:30pm and all have the word “CRASH” in capital letters added to the entries. After this, all is quiet until 1:00pm the following day, when routine operations resume. While these four were not the only victims directed to the Hospital or admitted to its wards, this is indicative of the level of seriousness of injury that the Cottage Hospital could process.

Our nurse continues “It was a dreadful day of course. Our small hospital could not cope with the enormity of the situation and although most casualties arrived at our hospital first, they were gradually sorted out and sent to other hospitals in the surrounding area.”

She continues, “There was an American Airforce base at Ruislip that contained a large hospital facility. They sent out a field hospital to the site and set up one of the earliest triage systems by sending casualties to the most appropriate hospital – bone injuries to Stanmore orthopaedic, burns to Mount Vernon and so on”. In letter to the British Medical Journal (BMJ), sent at the time, Doctors from Edgware General Hospital say they received 96 patients, of whom 54 were admitted on to the wards.

It seems that American service personnel were present at the accident and were able to call in their local medical staff to assist. The USAF approach in starting treatment at the crash site deferred from the approach of the fledging NHS (started in 1948) which expected ambulances to “scoop up” victims and transport them to Hospitals where the investigation of injuries and treatment would begin. Maybe the germ of the idea for the modern Paramedic started here.

Our nurse finally says “But Harrow still had some pretty badly injured people and the death toll was rising. One patient I will always remember was a young man. The impact had sent him into the coal tender and he had been buried alive there until he was dug out. He was not too badly injured, but he had coal dust buried into his skin and I spent the best part of the day extracting it. Unfortunately, some could not be removed and it was like he was tattooed”

The Harrow Observer and Gazette of 16th October 1952 ran a piece on the front page about local victims of the disaster. One of the trains involved had been a local commuter service.

This lists three local people as being detained in what it calls Harrow Hospital and names a further four who had been treated there. The article names a further 28 locals who had died.

Our Health Heroes exhibition on the history of Harrow Hospital opens on 25 October 2022.