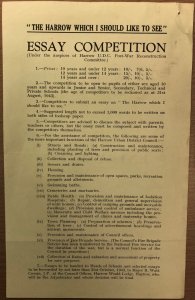

In celebration of National Storytelling Week (29th January to 5th February 2022), we’re delving into a treasure trove of essays from our archive that schoolchildren in Harrow wrote in 1943, painting a picture of their Harrow of the future in peacetime. Whilst still in the midst of war, and recognising a need to foster a sense of civic duty in young Harrovians for the benefit of the town’s regeneration, Harrow Urban District’s Reconstruction Committee asked children aged ten to seventeen to cast their minds towards a post-war civic ideal through an essay competition titled, “The Harrow Which I Should Like to See.”

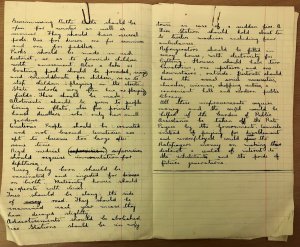

Clearly shaped by the careful oversight of teachers and guided by a series of bullet points provided to all essayists on the functions of the local council in civic life, many of these pieces are firmly grounded in the realities of the running of a town. However, amongst the sensible calls for wider roads and regular bin collection, emerge fascinating images of a future of the past: contrasting futures, that pit heritage against modernity; and both fanciful and unassuming futures that reveal the concerns and hopes of children living through an uncertain time.

Through these essays, we can even see parallels with the lives of children today, separated by almost eighty years, but again affected by a period of great uncertainty, this time due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

In this series of three blog posts, we will be exploring three of the overarching themes of the children’s essays – in the first, we will be looking at the tension the children’s views on the role of heritage, and the march of modernisation.

Modernisation Versus Preservation

The Harrow I would like to live in would be of peace-time days…you would be able to see the old street-lights and coloured lights that we see in the shops especially at Christmas time.” – John, aged 10, Longfield Middle School

A fair number of the essays feature St Mary’s Church as a focal point for the children’s thoughts on the relative merits of modernisation and preservation in Harrow. Many children agree that the iconic St Mary’s and its surrounding hillsides need to be protected from development at all costs, but what should be seen down below from the vantage point of the hill is far more up for debate. Some children call for a moratorium on housing development near the hill, to preserve a heritage view for this “glorious and beautiful” historic landmark, whilst others favour the sweeping destruction of all “Jerry-built” pre-war housing, to be replaced with primarily modern flats. It seems that Harrow could have become an icon of Brutalism – with just a smattering of detached houses on the outskirts for balance – if Harrow’s children had had their way. Patricia, aged 15, would have been bitterly disappointed to discover that the “dirty rows of dingy hovels” of West Street are not only still standing, but are now part of the hill’s conservation area!

The children could agree however on the aesthetic crimes of gasometers, with one boy lamenting that someone with “no sense of beauty” had spoilt the view from the hill. Sadly, they would need to wait until the arrival of a Waitrose in South Harrow in the 1990s to be rid of that particular eyesore that blighted Northolt Road.

Whether uniform flats for the masses or detached suburban paradises for the slightly more well-heeled, young Harrovians are also in agreement that homes of the future must be equipped with labour-saving devices and indoor lavatories. Patricia P., aged 15, looks to the States for her housing wish list, calling for British homes to adopt washing machines to help out housewives; no doubt the increased contact points with America, including American G.I.s and mass media, made Brits acutely aware of the domestic advances across the pond that made the UK look sorely behind the times.

Many young children have never seen street lamps alight but when they do may the Harrow that is lit up by them be worth seeing.” – Matthew, aged 13, Boys’ High School

Whilst some children espouse fairly extreme views of the level of ‘modernity’ Harrow should embrace, from razing everything to the ground and replacing it all with marvellous concrete, to preserving the last shreds of a rural idyll at the expense of practical housing, many admit to being unsure how to perfectly reconcile the needs of a growing population and the desire to keep the character of a Harrow from the past, and are glad they do not need to put their ideas into practice. Many town planners today could only wish that the stakes were as low as those of an essay competition!