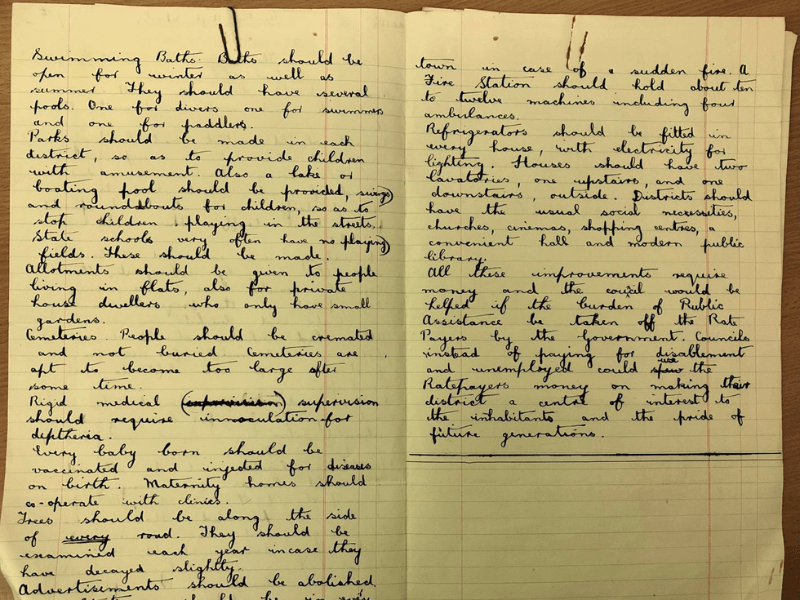

This is the third and final blog post delving into essays written by Harrow schoolchildren in 1943 for an essay competition run by Harrow’s Urban District Council’s Reconstruction Committee, titled, “The Harrow Which I Should Like to See.”

“They rebuilt Paris in fifteen years and I have been told that it is very lovely. Could Harrow be changed to a beautiful town in fifteen years, for I would not be very old if that happened, and should be so glad to live in a lovely town.”

Margaret, aged 11, Grimsdyke School

The war was undoubtedly a frightening time for children, but the essays written by Harrow’s schoolchildren are overwhelmingly optimistic, showing a great deal of resilience. The children even find the good in wartime life; ideas worthy of carrying forward into their new Harrow, such as ‘British Restaurants,’ heavily subsidised day nurseries,[1] and allotments. Multiple children speak fondly of the ‘British Restaurants’; John from Kenmore School argues that “the British Restaurant is a good idea” due to the excellent value of the meals, and Colin, aged 10, sees them as a chance for his mother to get out of the house. British Restaurants were communal kitchens, formally established in 1940 by the Ministry of Food, to ensure access to nutritional meals to all who could not source them themselves, be that due to bomb damage in their homes, or simply a lack of time for food preparation from war effort commitments outside of the home.[2] Unfortunately for the children’s vision for Harrow, British Restaurants did not remain part of the culinary landscape for long; these establishments were officially disbanded by the Government in 1947, and Harrow Council reluctantly closed the restaurants by early 1951, due to financial losses.[3]

The children of these essays seem remarkably resilient in other ways; take for example, Ralph, aged 10. In his essay, Ralph is able to list with equal importance a need for a Marks & Spencer and British Home Stores (BHS) in South Harrow, and the need for an air raid shelter to be adjoined to each house, because “there is a possibility of another war” – a suggestion that is presented in such a heart-wrenchingly matter-of-fact manner.

Whilst Ralph is keen to prep for a potential conflict, other children stress the importance of avoiding further war, and present a surprisingly empathetic, nuanced view of enemy countries. Patricia B. aged 15, looks to Germany for cultural inspiration, hoping to replicate the presence of an opera house in all towns, whilst R. Rizzi, also aged 15, urges,“…it must not be forgotten that there is much that we can learn (regarding reconstruction) from (foreign countries) as they can learn from us. I say this because if countries are to be friendly after this war, they must have a little more in common other than trading with each other.” Margaret, aged 11, suggests a way in which this mutual understanding could be achieved: “Harrow schools should have special holiday tours and trips to foreign countries. In return they should invite foreign children to Harrow, and entertain and amuse them. This would (help) us to get used to each other and stop future quarrels and wars.”

“Firstly the teeth. Why do people let their teeth go black? That is the question. They are too lazy to wash them….I think that after the war, when we go to the dentist…the surgeon ought to rub your teeth with the electric drill.”

Maurice, aged 10, Pinner Wood Junior Mixed School

Perhaps it is hard to gauge how optimistic Harrow’s children were about the possibilities of post-war life, and conversely just how badly affected the children were by their wartime experiences from these essays alone; many children would likely have felt the need to filter their thoughts and present a sensible and suitably optimistic essay that hit the points set out by the Urban District Council, if they had any hope of winning the prize money. However, there are some very disparaging comments aimed at the housing and services of Harrow, and some children certainly took this essay as an opportunity to vent about all sorts of topics only loosely related to the future of Harrow. Anne, aged 13, seems endlessly frustrated with the uncivilised behaviour of boys, both “little boys and big ones,” whilst Maurice, aged 10, laments the state of the nation’s teeth, warning, “after the war, when we go to the dentist…the surgeon ought to rub your teeth with the electric drill” for everyone being too lazy to brush them. These unguarded comments do suggest a certain degree of frankness, so we can perhaps infer that the children’s essays are representative of their feelings at the time, and that the children of Harrow were genuinely full of hope for the future of their home.

“Well that’s the Harrow I should like to see after the war! Let’s hope it will be!!!”

Maurice, aged 10, Pinner Wood Junior Mixed School

[1] For further reading on day nurseries, please see: https://eastendwomensmuseum.org/blog/2018/8/7/women-babies-and-bombs-how-day-nurseries-contributed-to-working-womens-lives-during-wwii

[2] https://www.findmypast.co.uk/blog/history/british-restaurants

[3] https://moderngov.harrow.gov.uk/Data/Council/19510113/Minutes/013_Civic%20Restaurants%20Committee_9%20January%201951.pdf